Protocols

for

Postcapitalist

Expression

Agency, finance and sociality

in the new economic space

Dick Bryan, Jorge López & Akseli Virtanen

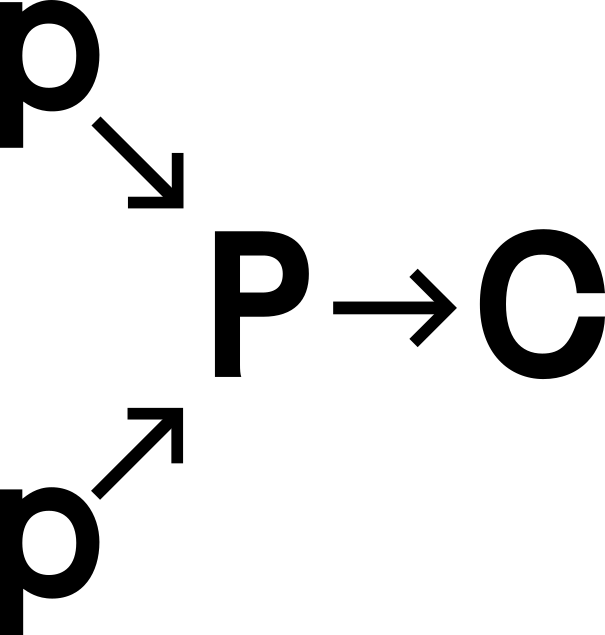

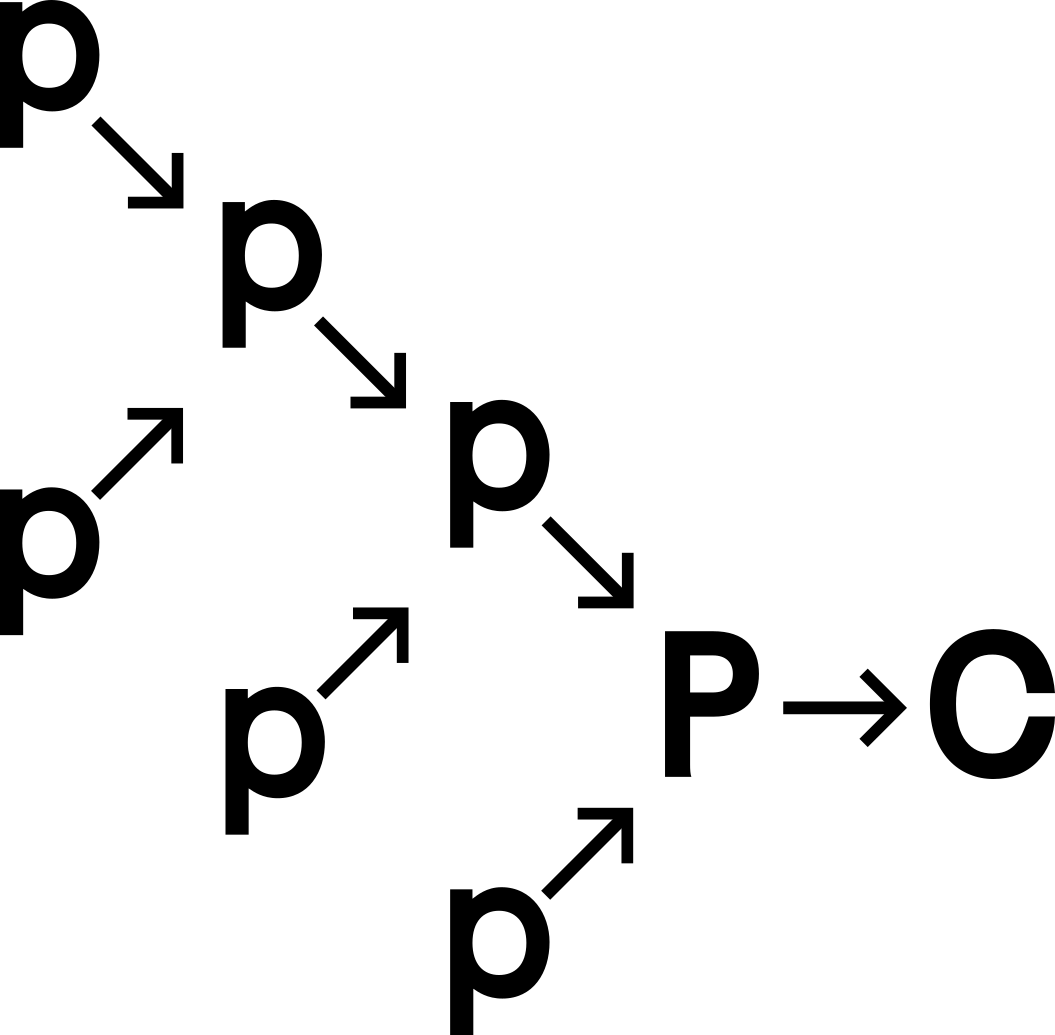

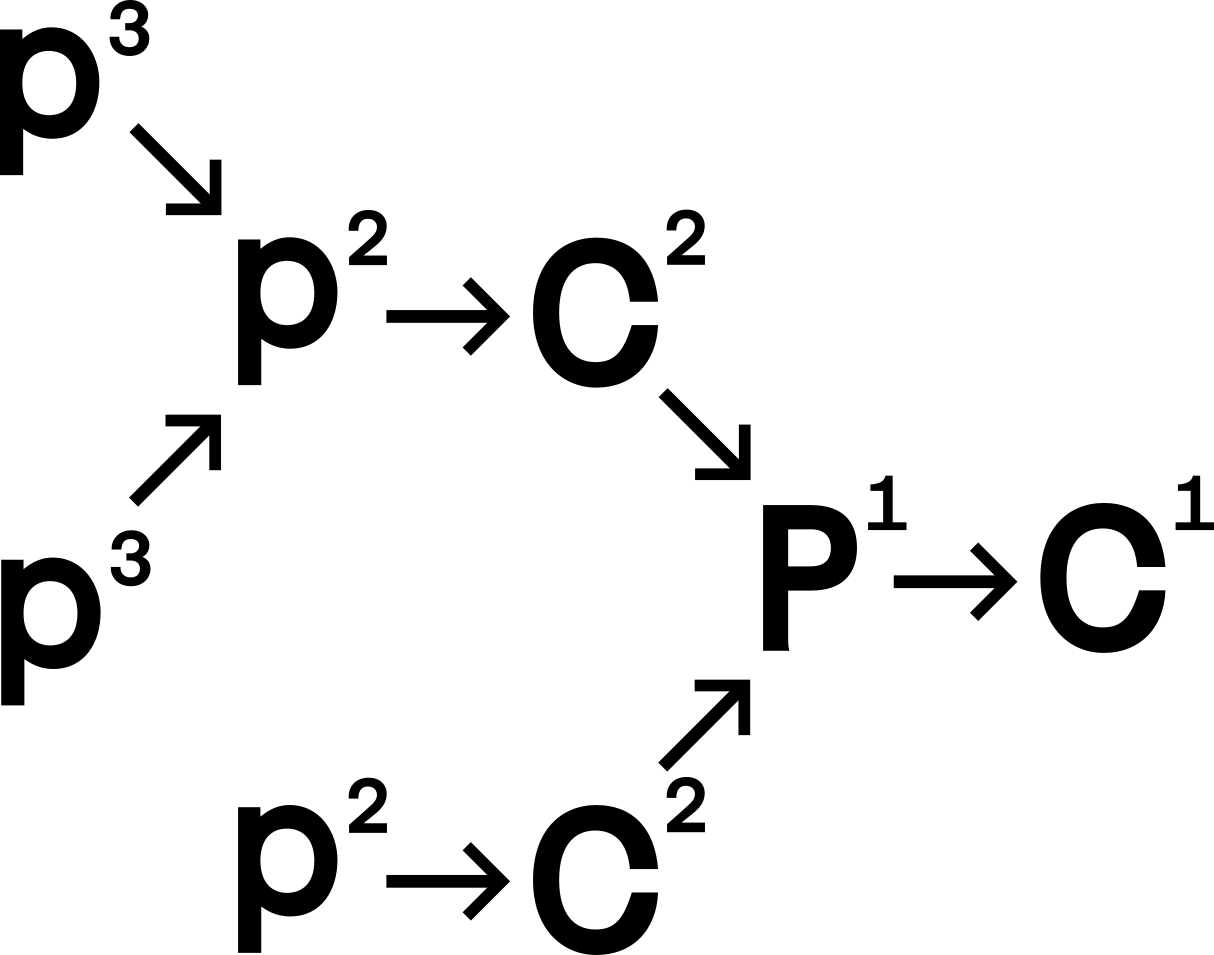

1Information has emerged dialectically as the most general form for the products of capitalism defined as having both use-value and exchange value. Because of its abstract character, it is often forgotten that information must have a material substrate, be it the standard commodity or an array of atoms on a computer chip. For the briefest of sketches, consider that the commodity was always composed of readable material differences, differences in matter created through labor. As a wager to get from M to M′, the commodity’s market legibility as a significant state of informed matter (a ‘hieroglyph’) has become increasingly computational. For my take on the networked commodity and the intimate connections between computing and capital see Beller (2017 and 2021). In each text I develop the argument that the general formula for capital can be rewritten M–I–M′, where M is money and I is information: Information replaces the commodity ‘C’ in Marx’s classic formulation M–C–M′.

2Whatever its specific embodiment, the sovereign subject that dominates Western philosophy is the subject of property. ‘He’ is semiotically, psychologically ideologically, and materially constituted through ‘his’ whiteness and cis-masculinity, the outputs of the representational and material systems that are among his dividends from colonization and slavery.

3Inspirational Marxist historian Eric Hobsbawm (1978) contended that the 1970s must be read as a crisis for working class organizations; a crisis from which they have not recovered. Our response is that collective endeavors that move beyond the control of capital must be focussed at the frontier of capitalist development—financial innovation—not in nostalgia for a resurgent industrial proletariat.

4‘If we don’t do this, we may not have an economy on Monday’ is a statement attributed to Federal Reserve Chairman, Ben Bernanke, in a meeting on Thursday September 18, 2008 with Treasury Secretary Henry Paulson and House Speaker Nancy Pelosi, in his advocacy of a $700 billion bailout plan for banks. https://www.nytimes.com/2008/10/02/business/02crisis.html

5Financial institutions in the period 2020–2022 might be depicted as financial terrorists, with sticks of illiquidity strapped to their chests, threatening to blow themselves up, and taking the rest of us with them, unless the state guaranteed market liquidity. And states gave those terrorists exactly what they wanted. The terrorist ransom payment is better known as Quantitative Easing, and because of it, the balance sheet of the Federal Reserve (to reference just one index) reached $8.9 trillion by mid 2022, up from $0.9 trillion in 2007, $2.3 trillion in December 2008, and $4.2 trillion in February 2020.

6Many people now make this argument. See, for example, Dixon (2018) and Buterin (2017)

7From our perspective, bitcoin identified the trusted intermediary component of capitalism. That is, capitalism’s regime of verification depends on trust which, in its turn, ultimately depends on states’ monopoly on violence and coercion. Bitcoin expressed that there can be more dimensions of freedom. It opened the question of the sociality of value: it showed that value is always social, organizational and institutional. But bitcoin didn’t give a language to express it. The Economic Space Protocol is a grammar for expressing the sociality of value.

8The trend to use equities as collateral for loans is increasingly prevalent. In 2017 the US Securities and Exchange Commission reconsidered the rules which prevented institutional market participants from pledging and accepting equity as collateral in the US securities lending market. In March 2020 the US Federal reserve, looking to rebuild liquidity in the Covid pandemic, enabled banks to borrow cash against stocks and corporate bonds.

9This term has been used in the ‘sharing economy’ literature for quite a few years. We use it here in a specifically blockchain-enabled way, as initially proposed by a local currency research team at Informal Systems. See, for example, https://cofi.informal.systems. See also Fleischman, et al (2020).

10Antonio Negri (1968) was astute when, in 1968, he observed that connecting the present to the future in a capitalist economy is the responsibility of the state. In the absence of this state role, we see the need to make the link financially will potentially be made by futures and option contracts.

11The argument here is crystalised in Chapter 8.5.

12See López, J. ‘Economic performance: The Economic Space Protocol.’ http://economicperformance.manifold.one. See Appendix 1.1 for a brief summary of its current application.

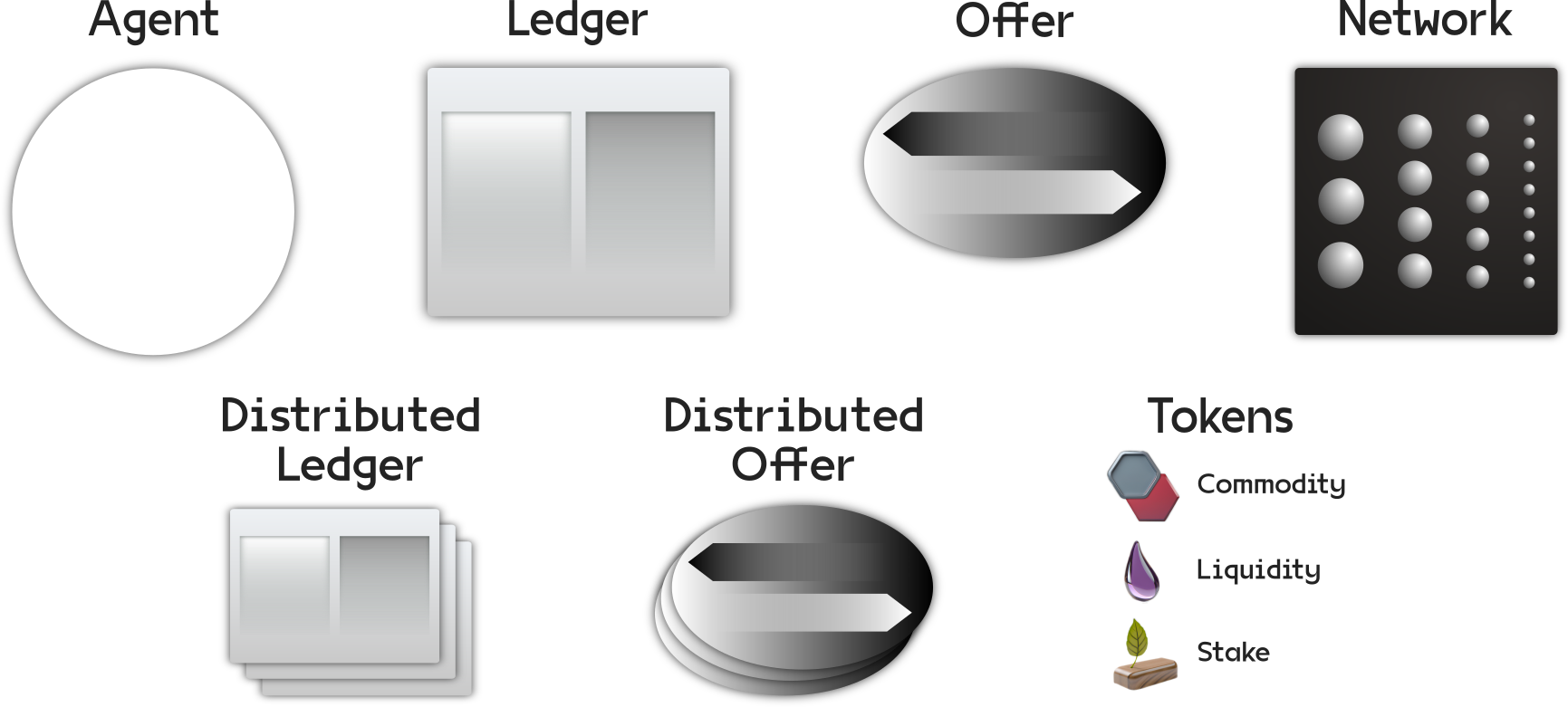

13Agents are defined more precisely in Chapter 3.2. In this context, they can be thought of as individuals or self-organized groups of individuals under a singular network identity.

14The distinctive meaning of a ‘performance,’ and its deeper significance, is elaborated in Chapter 4.

15Other forms of incentives, ownership and money do indeed exist within society but our point here is that capitalist incentives etc. are hegemonic and are expanding their reach into facets of daily life and social relations once seen as outside the economy.

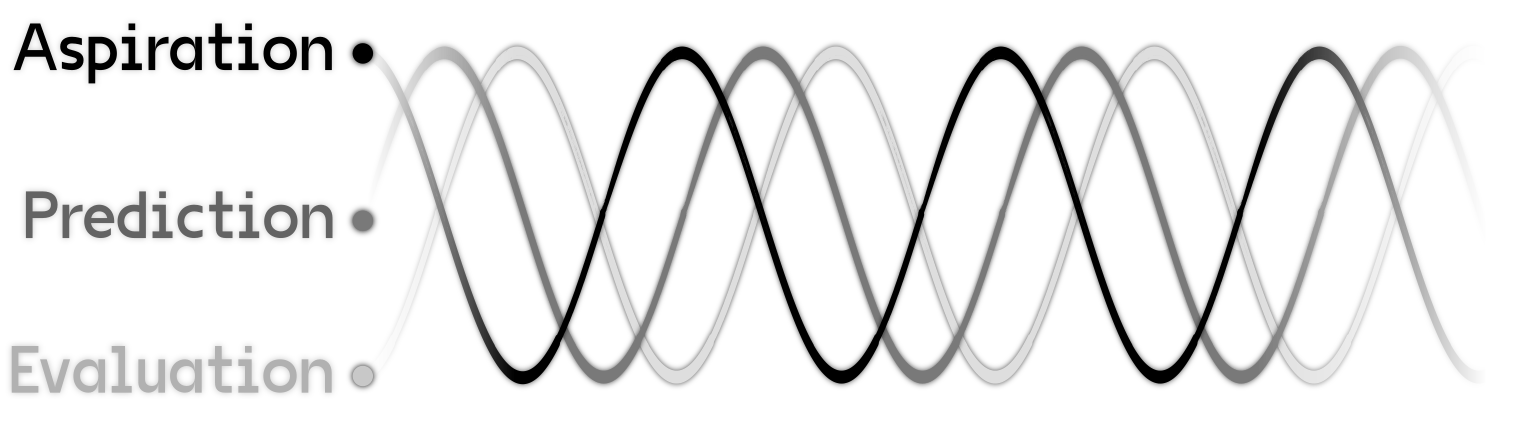

16The public policy literature discussed in Appendix 4.1 highlights the importance of the difference between outputs and the outcomes, or effects, of those outputs. Public policy is clearly more concerned to produce outcomes more than just outputs. Adopting the same framing, our use of the terms is that performances produce outputs but the network attributes value (it validates output) based on social outcomes. However, as will become apparent, it is necessary that ledgers record outputs, but these are always validated outputs (that is, they are recognized as having produced certain outcomes). When we describe the social contribution of performances, the focus will be on outcomes; when we describe the ledger processes, the focus will be on outputs, but the latter always presumes network-validated outcomes. This process is described in Chapter 4.

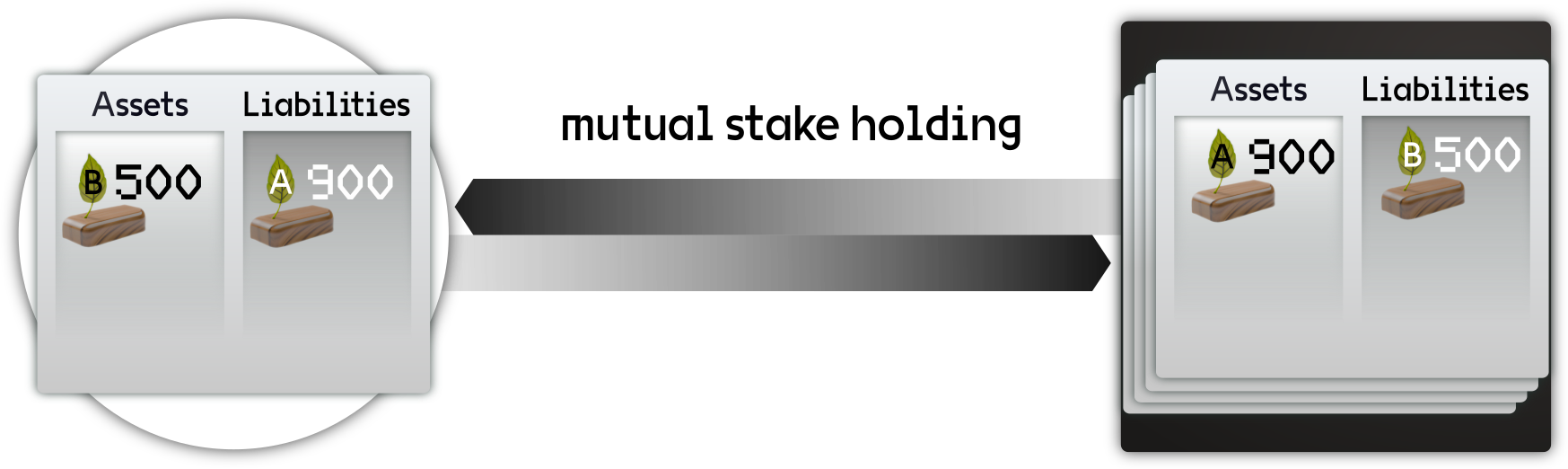

17The way in which mutual staking forms a commons is addressed in Chapter 6.

18In the focus on alternative notions of value, staking could be seen as an act of partial or full philanthropy. In that framing, the staker may simply want the performance and its outputs to be realized because they are a ‘good cause.’ The network will indeed collect data on these philanthropic stakings, and there may appear correlations/causations that reveal a wider social benefit attributable to such performances. These performances may indeed find recognition in the network as value-creating, even when this is not the intention of the performing agents. But the network is not defined by philanthropy: it is defined by value creation and returns for value creation, where the distinctive feature is that the products of performances can create collectively defined value even when they create no profit.

19The ECSA Glossary is available at https://glossary.ecsa.io/.

20The need to cut energy usage in ordering transactions on a blockchain has seen the system of verification shift rapidly from proof-of-work to proof-of-stake.

21Staking, in this sense, is often also incentivized by (often absurd) returns in the protocol native token, or in the protocol’s native token in combination with some other protocol’s token.

22For example, vote-escrowed governance tokens, or some other ‘rights,’ largely depending on the amount and the length of staking time.

23This issue is addressed in Chapter 7.

24Stripped to its basics, the liquidity premium is a cost that addresses the deepest, darkest fear of capitalism: that the market (people to sell to or buy from) will simply disappear in sufficient numbers so that the flow will stop. This point, and the necessity of the dealer function, has been emphasized to us by Colin Drumm (2021), see also Treynor (1987).

25For explanation see López, J. ‘Market credit: Distributed liquidity protocol.’ http://marketcredit.manifold.one

26This is the practice of shadow banking. Many people equate shadow banking with illegality. But investment banks like Goldman Sachs, insurance and reinsurance companies and money market funds—many of which are divisions of large ‘standard’ banks—engage in shadow banking, where the feature of being outside standard regulation is that lending is fully collateralized.

27A unit of value will be explained in Chapter 6.3. Suffice it here to define it as a socially/ historically specific system of measurement.

28There can be an argument that the concept of ‘profit’ is not specific to capitalism; what is specific is the way profits are calculated. We have chosen to adopt the word ‘surplus’ in relation to the Economic Space Protocol to avoid ambiguity. See Appendix 5.2 for elaboration.

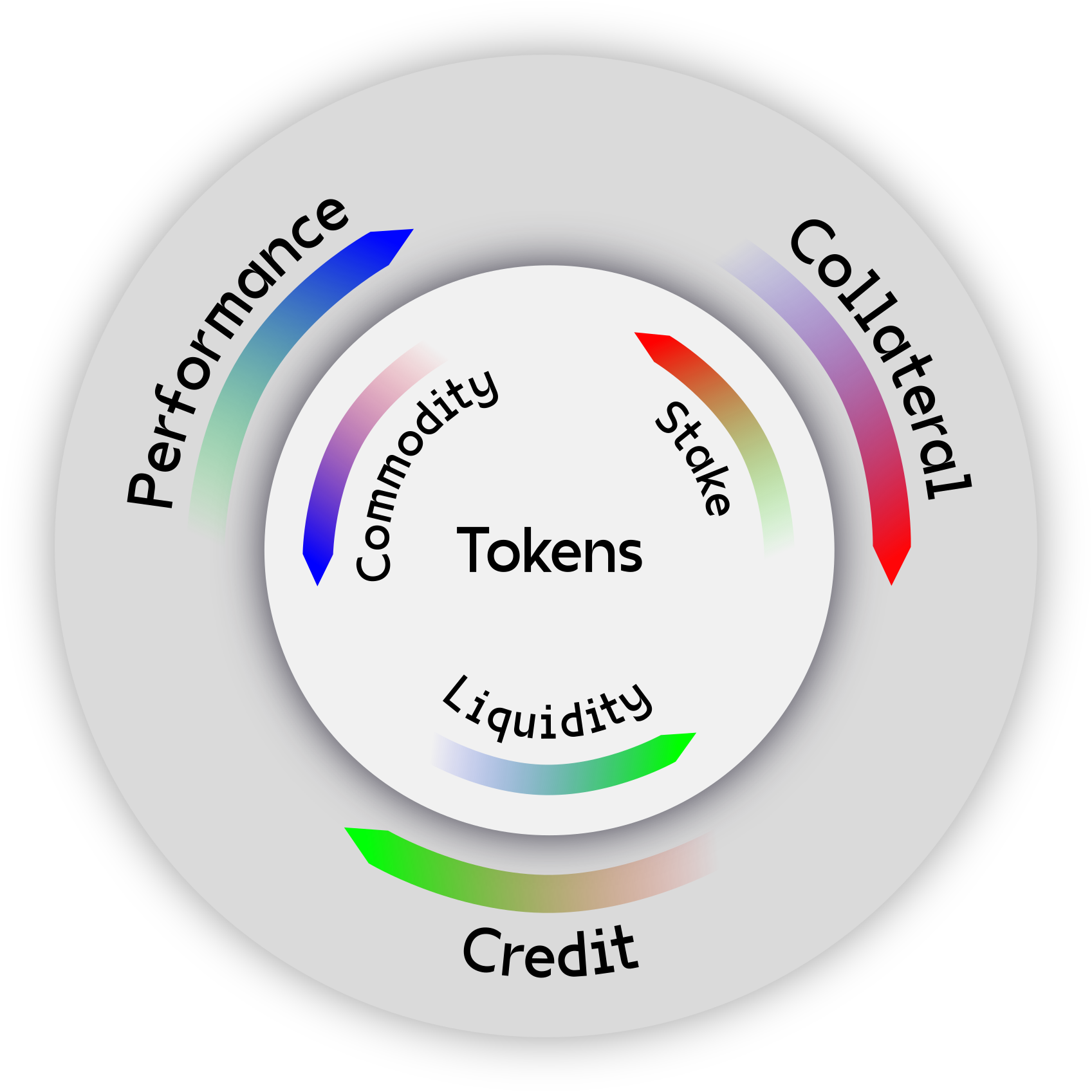

29We note the blurring of the categories of money and assets. One form of blurring is between debt (money) and equity (assets) (e.g. convertible bonds). Another is found in central bank policies of Quantitative Easing, and the expanding range of assets central banks are taking onto their books in the name of ‘monetary policy.’ The blurring was noted by Myron Scholes (1997) in his Nobel Prize lecture.

30Toporowski (2010: 12) puts it succinctly: ‘in an era of finance, finance mostly finances finance.’

31Named after economist Hyman Minsky, a ‘Minsky moment’ is a sudden collapse of asset values which becomes self-perpetuating. Collapses in asset values collapses the value of collateral leading to margin calls and the sudden loss of capacity to support loans.

32Randy Martin was a friend and mentor to many of us in ECSA. He has inspired our vision and our analytical techniques. Randy died before the real emergence of crypto technology. His brilliance would have at once embraced the social and political potential of cryptomedia choreographies. See, for example, Martin (2013, 2014a, 2014b, 2015) and Lee and Martin (2016).

33In finance, a derivative involves the purchase of an exposure to the ‘value’ of an underlying asset without (necessarily) purchasing ownership of the underlying asset itself. Derivatives therefore trade risk positions: the risk of the price of a barrel of oil going up or down, without trading the barrel of oil. Options, as critical forms of derivative, enable the coverage of risk in one direction, but not the other: they can insure against prices going up, or they can insure against prices.

34See López, J. ‘DJS: Distributed Javascript.’ http://djs.manifold.one

35For example, the liquidity token allows the user to exchange and clear commodity tokens. The stake token enables users to peer with others to create economic relationships through reciprocal mutual stakeholding.

36The International Monetary Fund reports that, in 2022, 105 countries and currency unions are exploring central bank digital currencies (up from 35 in 2020; 19 of the richest 20 currencies are involved—see Fanti et al (2022)).

37We already see, to quote Nick Land (2018, §2.653), if human beings are found to be irrational or incompetent or ‘lack the plasticity to compete in these terms, or revolt against the roles and templates being automatically laid-out for them, then artificial agencies—‘DAOs’—will be fabricated to play the game instead.’

38For example, Nick Szabo tweeted about economists and programmers: ‘An economist or programmer who hasn’t studied much computer science, including cryptography, but guesses about it, cannot design or build a long-term successful cryptocurrency. A computer scientist and programmer who hasn’t studied much economics, but applies common sense, can.’ @NickSzabo4, March 23 2018 https://twitter.com/nickszabo4/status/977035747713675264

39Not least because these technologies exist in abundance, with marginal costs effectively zero.

40Milton Friedman later called it the tyranny of the majority: that an elected government could claim legitimacy in trampling on people’s natural rights. For some, quadratic voting offers an alternative.

41Albeit that they tend to ignore the later Hayek’s more nuanced view of markets, and the recognition that the state always plays critical roles of market facilitation.

42There are current critiques of capitalism that feature the proposition that capitalist markets ignore ‘externalities’ (costs and revenues that are not allocated within existing property relations). The classic case is pollution, which imposes social costs that are not borne by the polluter. We concur that this failure is significant, but contend that if we focus on this ‘flaw,’ then we are implicitly conceding that, in the absence of externalities, capitalist markets warrant our affirmation. Our critique is that they privilege profitability and individualism over other values and collective benefit, whether or not there are externalities.

43See Bernes (2020), for an impressive recent contribution. Some have argued that global corporations are applying all the techniques that would be required for state-run central planning. See, for example, Phillips and Rozworski (2019).

44Market Socialism sought to integrate private enterprise or capitalist modes of calculation within socialist planning, generally by the operation of markets at the ‘local’ level, with market information guiding central planners in the ‘big’ allocation decisions. This intervention in the Socialist Calculation Debate is associated especially with Ota Šik, economist and deputy Prime Minister of Czechoslovakia, who was central to the liberalization of the Czech economy and the ‘Prague Spring’ that triggered the Soviet invasion in 1968. Capitalist modes of calculus, via the use of changes in stocks rather than prices to determine output decisions, is associated with post-war Polish economist Oskar Lange.

Our concern is not balance between planning and markets, for we believe it to be a false juxtaposition, but with the protocols under which markets are conceived. But it should be noted that this literature precipitated Hayek’s break with neo-classicals: both their conception of ‘competition’ and their belief in ‘equilibrium.’

45Hayek’s explicit reference to a means-end structure signals that the ends are beyond evaluation.

46Morozov (2019) contends it is just a neoclassical interpretation of Hayek that argues all information reduces to price.

47For example, when I pay $5 for a cup of coffee I am not actually going through a complex calculation of the costs of all the technologies, raw materials, transport, labor, taxes, consumer preferences etc. that lie behind a cup of coffee. I just reduce all that to the acceptance of the price, pass over the debit card, and receive the coffee.

48This is the perfect word in this context, but it is not in common usage, so we offer a definition. A velleity is a wish or inclination not strong enough to lead to action.

49Financial market models that attempt this reverse engineering are at best crude, and were not envisioned by Hayek.

50We note the short term supply condition of covering fixed costs, so ours is a longer-term and more general proposition.

51The work of R.A Bryer is particularly important in this analysis. See https://www.researchgate.net/scientific-contributions/RA-Bryer-2003195221. For a summary of and insight on the literature accounting and capitalism, see Chiapello (2007) and Chapter 6.3.

52Indeed, it was not until the middle of the 19th century and the rise of joint stock companies (ownership diversified through a stock exchange), that the rules of these accounts became generalized. In essence, owners and prospective owners needed reputable information on which to base their decisions to buy and sell.

53Of course these outputs can be designed for commercial sale, but that will capture only a fraction of their social contribution/collective value.

54At this point in the analysis, a surplus can be taken to mean any excess over what is required to reproduce the current conditions of the network. It is usually thought in financial terms (profit rent, interest) or commodity outputs in excess of commodity inputs (e.g. Sraffa, 1960). We will later invoke broader, more social perspectives on ‘surplus.’

55See, for example Goldman Sachs analyst (later Professor of Financial Engineering at Columbia University) Emanuel Derman (2002) says of short-term investors: ‘They may perceive and experience the risk and return of a stock in intrinsic time, a dimensionless time scale that counts the number of trading opportunities that occur, but pays no attention to the calendar time that passes between them.’

56Reference here is to Henri Bergson’s (1889) framing of duration, further developed by Deleuze (1988). The critical point is that the time of change and event cannot be reduced to its preconditions, thus going beyond a linear (and spatial) conception of time.

57This process depicts the network as if it were, in key respects, an automated market maker: an agency which executes orders on behalf of agents in the network.

58In Marx’s depiction of capitalism, this dynamic is expressed as the pursuit by capital of relative surplus value (growing profit from changing the conditions of production: a creative but nonetheless extractive logic). But if we take innovation out of the discourse of profit-seeking capitalism, it is the momentum to pursue many, diverse developments, consistent with the values expressed by the network, that will enable the expanded reproduction of the system.

59It follows that we can think of Hayek’s price as itself a derivative on those underlying forms of information of which price is said to be the condensate. In Hayek’s analysis, ‘price’ is really the strike price on the option on a synthetic asset called ‘knowledge.’

60For Hayek, and Keynesian economics, the story of liquidity ties to agents’ desires to hold liquid or illiquid assets and the capacity of the rate of interest to impact that choice.

61In Marx, too, the existence of a bid-ask spread creates challenges in the depiction of price in relation to value. We thank Colin Drumm for this point.

62We nominate this book amongst a range of recent contributions about the implications of big data for understanding the future of capitalism because of its claims to significance. The original German version is titled Das Data; a play on Marx’s Das Kapital.

63A parallel proposition in relation to capitalism is that competition for technical change (motivated by cost cutting, new product design, etc.) is of greater long-term significance than competition over prices in a market. Indeed, history shows that the great monopolies/oligopolies of history are defeated by being technologically superseded, not by competition from lower cost providers. We do not believe that data will somehow sit alongside price as an additional input to decision making, for within conventional calculus data will predictably be incorporated into pricing, and product design (and marketing) will become more differentiated in response to the patterned diversity revealed in data. We concur that the role of capitalist money will indeed be challenged. Yet the challenge will not be by recourse to an amorphous mass of statistics. It will occur via the invention of new, different indices: new modes of ‘money’ (tokens) expressing different social knowledges.

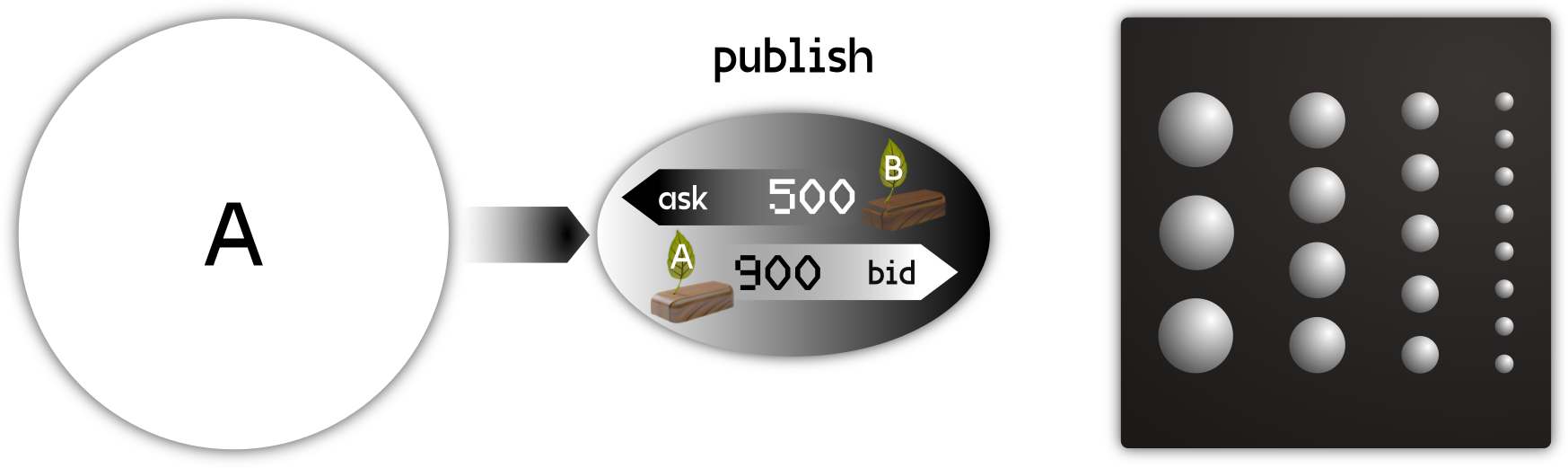

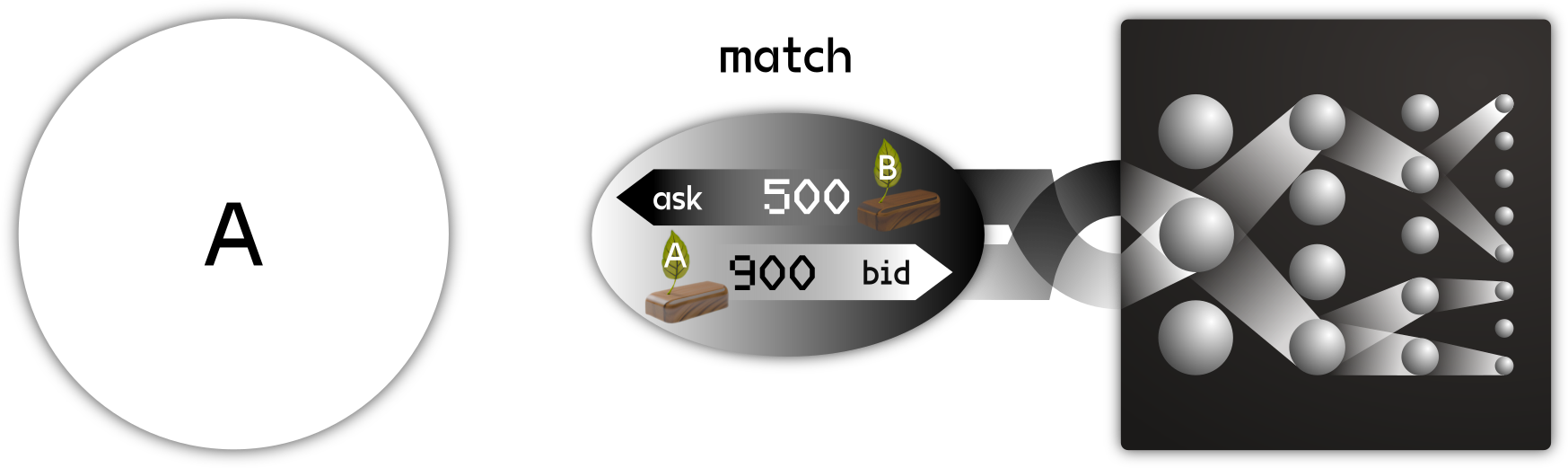

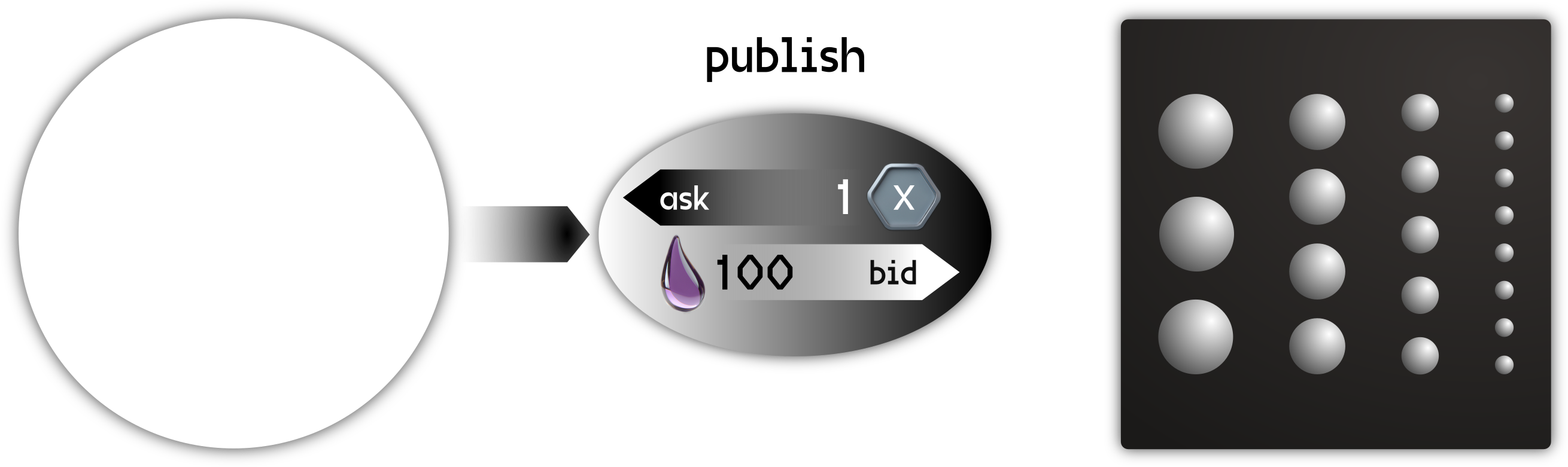

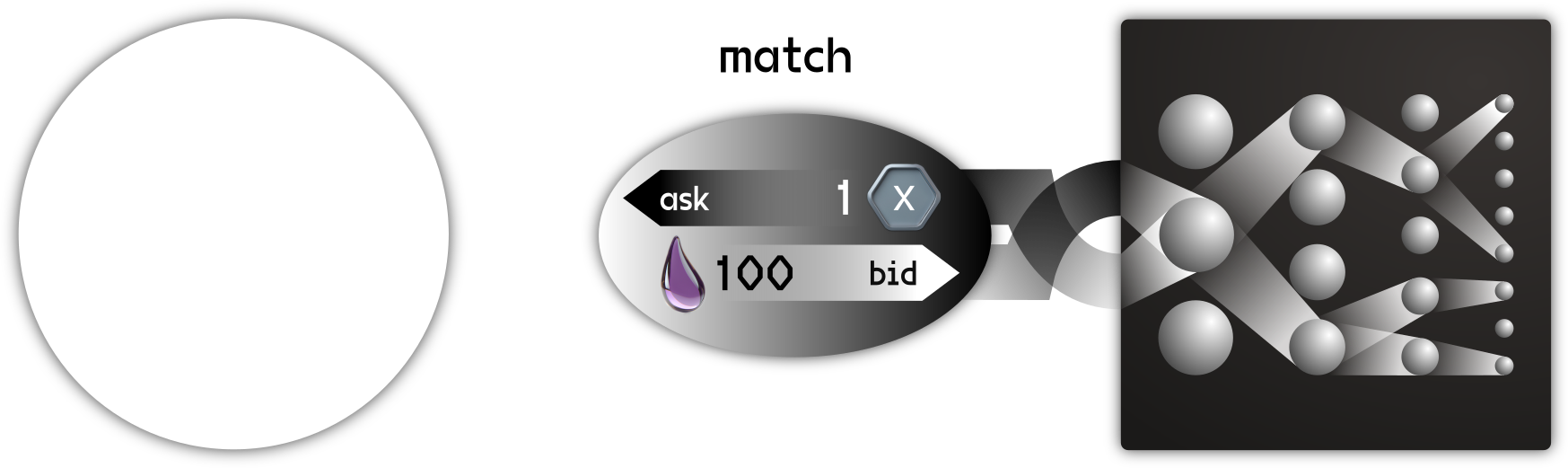

64See Chapter 4.4 for some consideration of internally-generated data, although this analysis is not intended as an engagement with social debates about big data.

65Keynes wrote his General Theory (1936), which transformed economic policy in the mid 20th century, without use of data. His view was that the economic data which were collected at the time were assembled in taxonomies incompatible with his new theory. Empirical Keynesianism awaited the development of national accounts compiled in ‘Keynesian’ categories.

66Morozov (2019) has drawn attention to the seemingly-neglected work of Daniel Saros (2014). Saros develops important insights on the use of big data in decentralized planning. While written without reference to crypto and blockchain, it is clearly blockchain-relevant.

67Those who oppose market relations (and generally also the adoption of token exchange) generally also advocate localism, where it is direct personal relationships, not in a record-keeping system that form the basis of trust. The inevitable neglect of the production process that cannot exist without scale is clear, so this perspective is not engaged in our analysis. Furthermore, local relations are never without their own power relations.

68In Marxism, one way of depicting the so-called ‘transformation problem’ is the challenge of reconciling value defined in simple exchange with value defined in dynamic accumulation of capital.

69Critics of Marx would say that the need to reconcile every commodity’s value denominated in labor time with a market price is the technical flaw in Marx’s analysis: the so-called ‘transformation problem.’

70The contrast in both cases is with an individual defined autonomously, outside of social context.

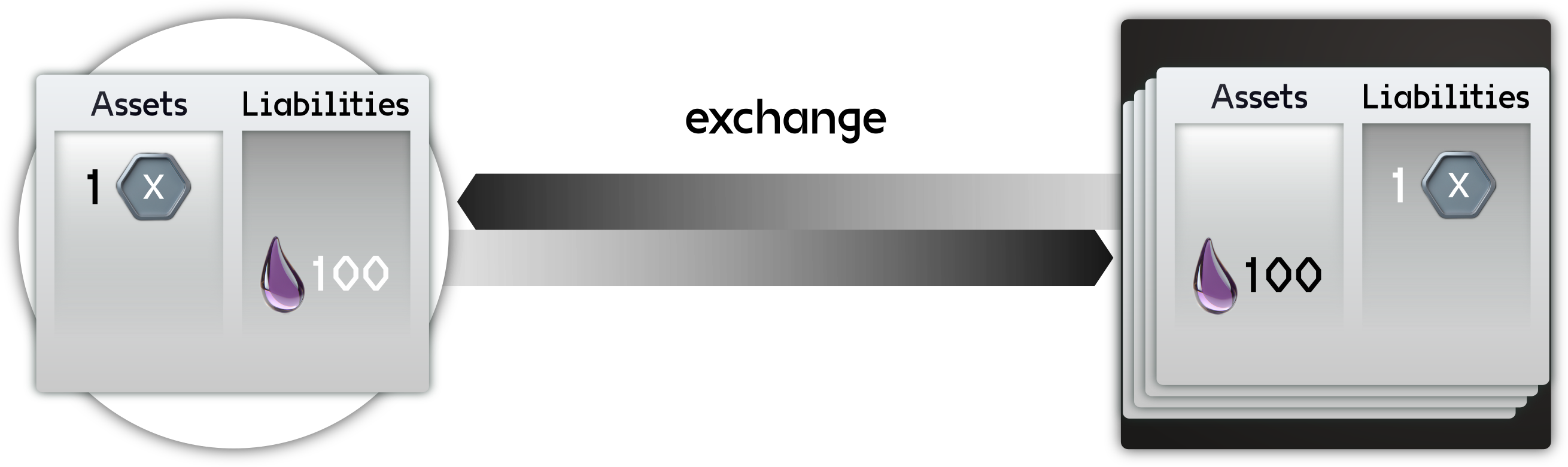

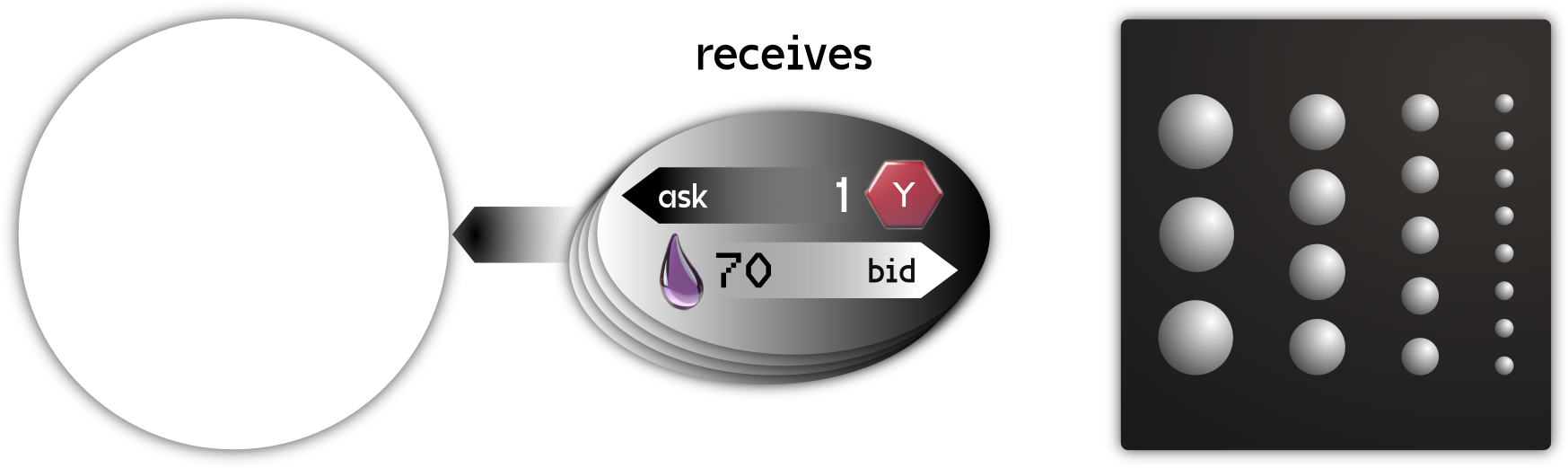

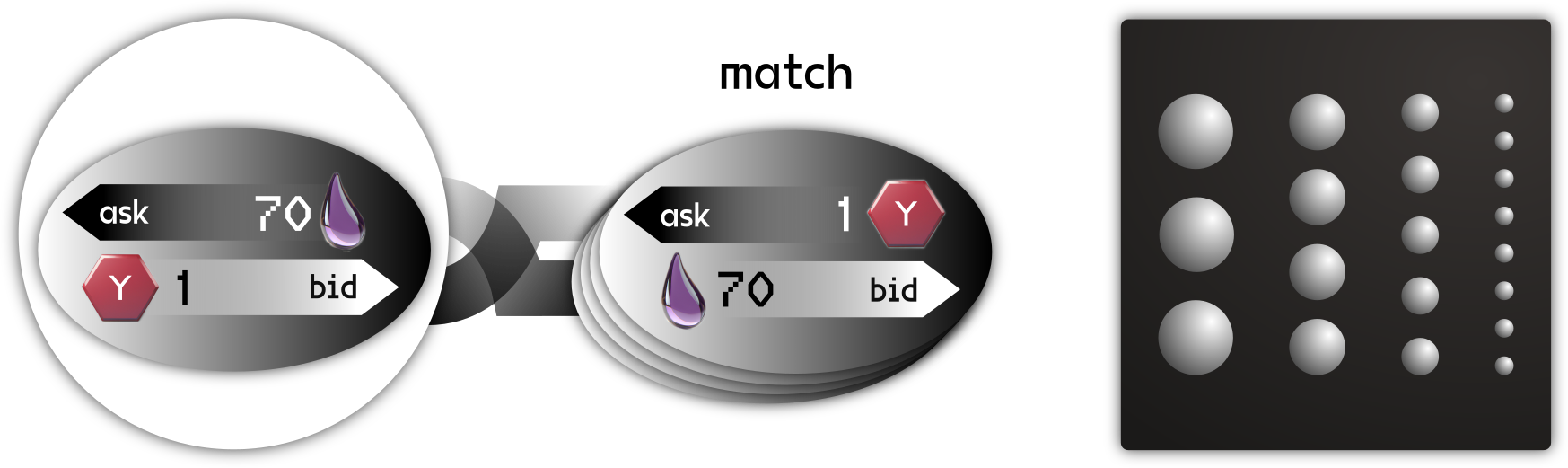

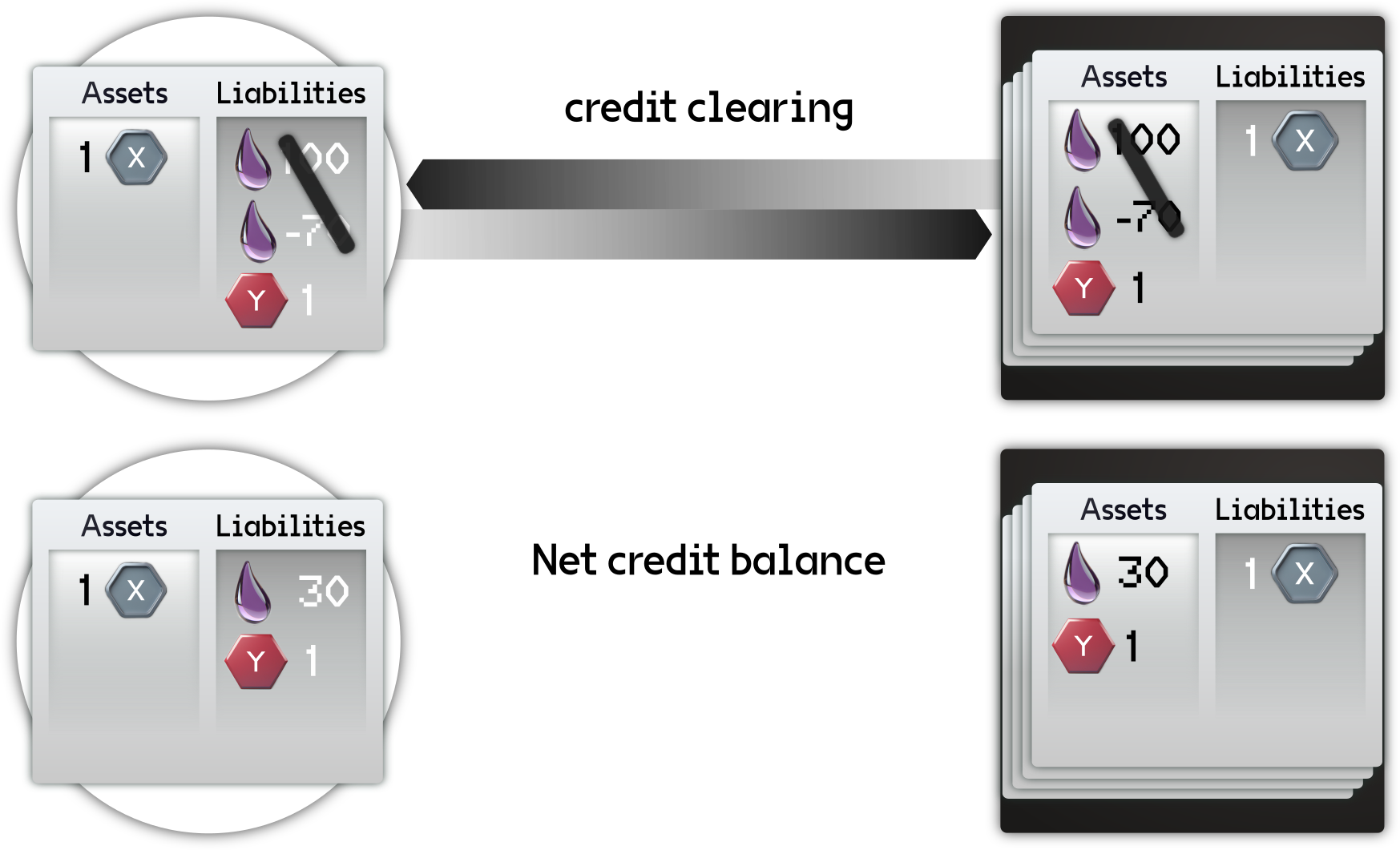

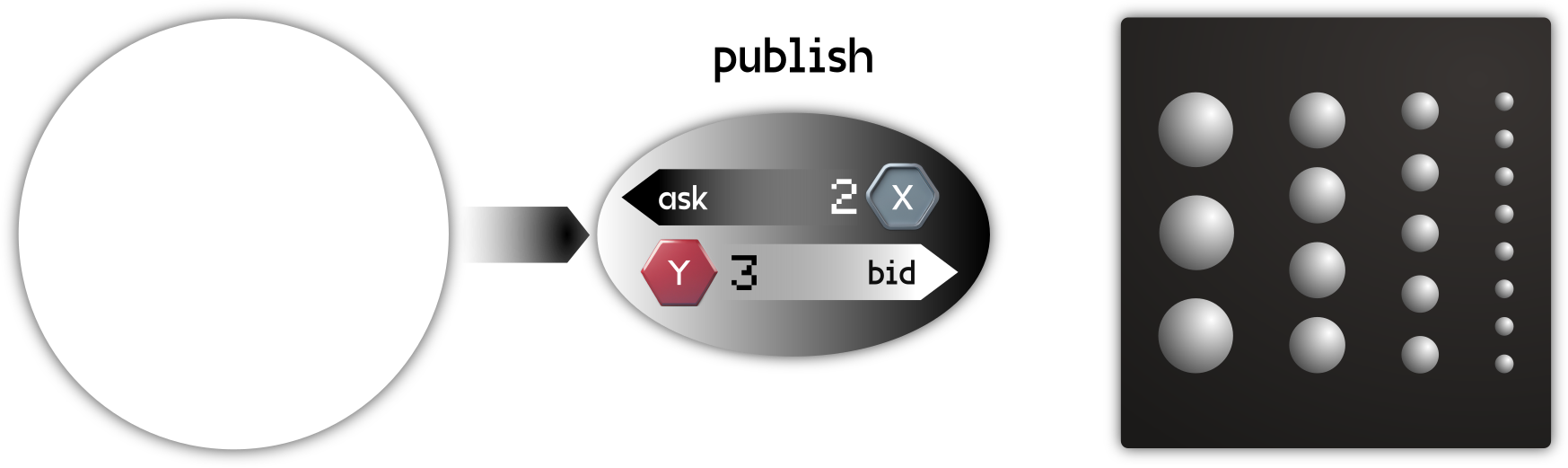

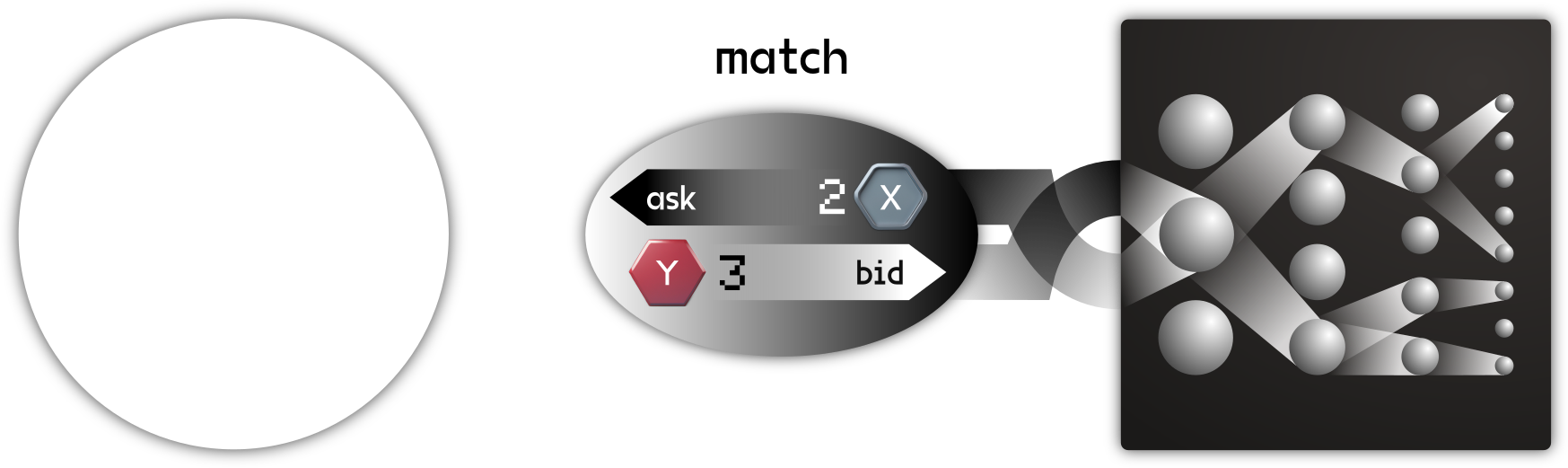

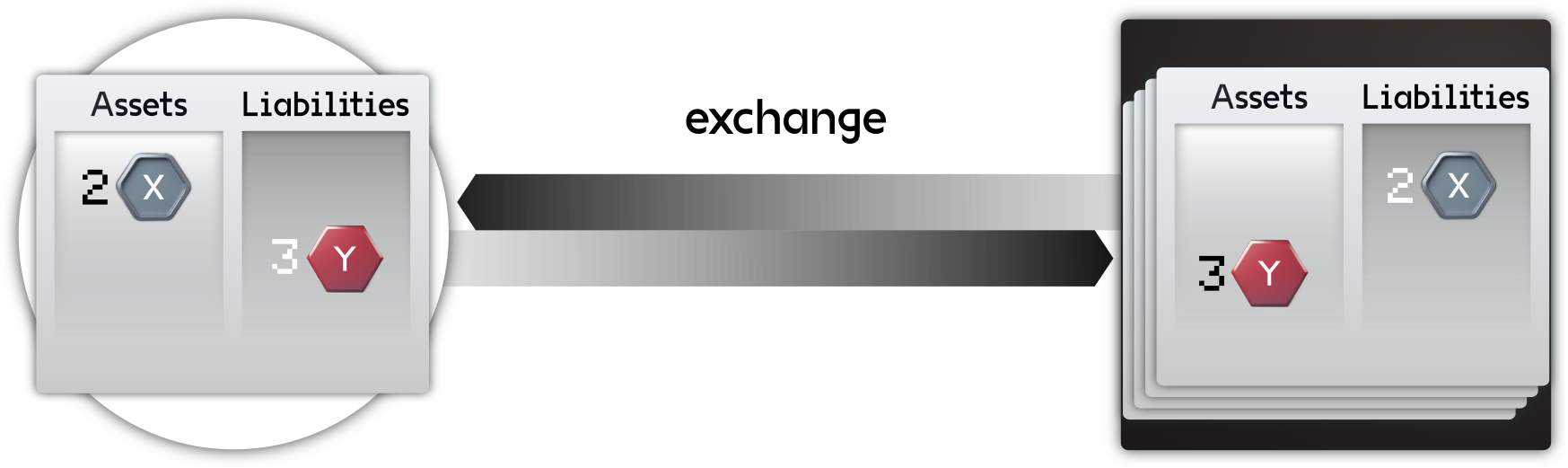

71Offers and matching are explained in more detail in Chapters 9 and 10.

72See López J. ‘Market offers: Distributed trading protocol.’ http://marketoffers.manifold.one

73This is the first use of the term ‘commodity,’ which appears frequently in the following analysis. We define ‘commodities’ to include all outputs produced for, and recognized by, the network. It is not Marx’s use of the term, which associates commodities with capitalist production relations. There, commodity production has two dimensions: it is extractive, in the sense that commodities are produced by the workers and owned by the capitalist, and it is produced so as to be sold for a profit. This latter emphasis gives rise to the term ‘commodification,’ with more and more facets of social life converted into marketable opportunities for extraction. Our use of the term ‘commodity’ is more like Sraffa (1960) in his book Production of Commodities by Means of Commodities. There, commodities are all produced outputs. They are produced for a market, but they are not exchanged for money. This gives space for our proposition that commodities can be produced for the commons (without a price). Similarly, there can be no suggestion that our use of the term commodity is subject to a ‘fetishism’ of commodities, developed by Marx (1867) at the end Chapter 1 of Volume I of Capital, for this term, too, is capitalist-specific. In many analyses, the political response to fetishism is to take goods and services out of market relations. Our proposal is to change the nature of markets.

74The formal explanation of a unit of exchange is developed in Chapter 7.

75This issue is explored in Chapter 10.

76The term ‘chartalism’ to describe state-issuance of money comes from the Latin ‘charta,’ meaning ‘ticket’ or ‘token’; indicating that money is a type of token.

77In the terminology of Gurley and Shaw (1960) third party issued monies like fiat currency and bitcoin are ‘outside money.’ Outside money may certainly enter the new economic space, but it will do so as a commodity for exchange. A transfer of outside money within the network will be matched by a token transfer, as it is for any commodity exchange.

78Hayek and indeed all ‘neoliberal’ economics advocates decentralized markets, with some conditions of ‘market failure’ and exceptional use of an active centralized agent. Hayek wanted the money used in exchange to be decentralized; the neoclassicals want it centralized.

79The effect is a distributed economic intellect, referring to Marx’s notion of the general intellect, which in its turn refers to the final phase of capitalism, where capital itself generates the seed of its destruction when knowledge and social powers of interaction replace direct labor and labor time at the core of the production of wealth. See Virtanen (2006).

80Stakers could, for this purpose, be considered participants. They could make their staking conditional on the performance offer having a certain structure, including its social relations in production. Furthermore, we expect performing relations to become a new value layer: a critical performance outcome.

81See López, J. ‘Network Performance: Distributed Computing Protocol.’ http://network-performance.manifold.one

82The network holds all records, of which the ledger is just one type; for example, records of offers made, even if they do not get a match. Moreover, it warrants emphasizing that it is performances that encode information with meaning.

83By ‘+’ in this context we mean simply ‘in combination with,’ where combinations may be expressed in any way that is deemed to have economic significance.

84Sraffa (1960) proposes a Marx-compatible approach to value that is not centered on labor time. We admire this work as opening a way of framing value in a postcapitalist economy. In acknowledging Sraffa, we might call our own approach ‘production of performances by means of performances.’

85The proposition is not that labor theories of value cannot explain intangibles like software, for the labor of the software designer could indeed be counted. It is that little about the significance of software in value formation is going to be explained by this attribution.

86We are aware of Marx’s concept of socially necessary labor time, making acceptance of a commodity in the market a condition of value. The point here is consistent with that condition of value.

87We acknowledge here the contribution of Pamela Hansford who brought this literature to our attention and advised on its application.

88Social impact bonds are said to have been first invented by a New Zealand economist Ronnie Horesh in 1988.

89In practice, the investors do not lose all their money. Governments’ desires to promote the policy have tended to set generous terms for investors.

90Social impact bonds involve the government funding an experimental intervention to determine whether it should receive on-going state funding. They were never designed to be on-going modes of service provision, for a repeat of the same intervention involves no calculation of investor risk, and hence no rationale for investor return.

91The questions of how, when and how often to measure outcomes have become big questions in public sector use of the evaluation framework, as they will be in a new economic space.

91For Marx, this stage was directly contingent on advanced technology developed in capitalism and involved the proletariat freeing itself of capitalist class relations so that this individual expressiveness and free association could flourish. This technological development and its social conditions Marx referred to the ‘force of production’ or ‘productive forces.’ In the words of Marx:

The appropriation of these forces [of production] is itself nothing more than the development of the individual capacities corresponding to the material instruments of production. The appropriation of a totality of instruments of production is, for this very reason, the development of a totality of capacities in the individuals themselves . . . .This appropriation is further determined by the manner in which it must be effected through a union Only at this stage does self-activity coincide with material life, which corresponds with the development of individuals into complete individuals and the casting off of all natural limitations. (Marx 1854, Part 1, Section D)

93There is nonetheless ambiguity here, especially about how profit is defined and the time horizon for profit maximization.

94The mechanics of this process are examined in Chapter 10.2.

95See López, J. ‘Market shares: Distributed Staking Protocol.’ http://marketshares.manifold.one

96Something approximating this statement appears in Graham and David Dodd’s 1934 book Security Analysis: the original text on investing according to a company’s ‘fundamentals.’ The specific statement, however, is not in the book. It is often simply attributed to Graham, most notably by one of his students, Warren Buffett. See also Appendix 5.3 for elaboration.

97The focus here is on outputs (for they are what is recorded in the ledger) although reference is to outputs whose outcomes have been validated by the network.

98See Appendix 5.2 for elaboration.

99See Chapter 1.4 for this differentiation.

100Graham was Warren Buffett’s teacher/mentor. Buffett has written an introduction to later editions of Security Analysis.

101Tesla did not turn a profit between 2002 and 2019 yet its capital value was greater than Toyota, despite the fact that it produced less than 5 percent of the number of vehicles produced by Toyota.

102The proportion of these companies’ assets classified as intangible is: Alphabet, 73 percent; Amazon, 81 percent; Apple, 96 percent; Microsoft, 93 percent; and Tesla 94 percent. See Brand Finance (2022).

103Reference here is to the emergence of so-called ESG accounting to sit along profit and loss accounts. But as ESG accounts are scarcely quantified, they sit largely as ethical qualifiers to standard accounts; not as an alternative way of measuring.

104Sraffa was not particularly an advocate of ‘market socialism’: a term which arose in the context of the 1920s Socialist Calculation Debate which Hayek claimed to have mastered (see Chapter 2.4). The proposition here is simply that he describes a surplus that could be framed in the context of ‘market socialism.’

105The Creative Commons, for example, issues licenses to enable free distribution of an author’s work for its further development. The license can limit the uses to which their work may be applied. See https://creativecommons.org.

106Direct staking is when two parties own a stake in each other. Transitive staking is where one party holds a staking exposure to another via a third party. If A holds stake in B and B holds stake in C, then A has a transitive staking exposure to C.

107The owners of stake in these performances receive yield in the form of appreciating stake price, but no private dividends. It could be that each individual investor is prepared to forgo yield because of a commitment to the commons. Or it could be that this commitment is shared across the network, and demand for stake in these performances sees stake price escalate to ‘compensate,’ as it were, for the lack of private dividends.

108‘Not paid for’ should not create the impression that it only applies to the outputs which would ‘normally’ be sold. Perhaps a better term is that applies to outputs that can be attributed only a synthetic price, as per Chapter 4.3.

109Will any agent see a disincentive to hold stake in a performance which issues dividends to the commons, because they lose access to privately-accruing dividends? This would be a narrow reading of incentives, for to hold no stake in commons-linked performances would see this agent having limited access to the assets and products of the commons. So if the network as a whole judges a performance to be value-creating for the network, and its dividends are issued to the commons, each individual agent must hold some stake in that asset, directly or transitively, to access any part of the commons.

109Reference here is to Marx’s slogan from his 1875 Critique of the Gotha Programme (part 1):

‘From each according to his ability, to each according to his needs.’

111The possibility of decay to the commons, as a way to deal with the wealth effects of diverging stake prices, was raised in Chapter 5.2.

112In the Socialist Calculation Debate, the principal area of disagreement between the advocates of central planning was what units should be recorded on ledgers: price or units of labor time or actual physical magnitudes of outputs and costs (called calculation in-natura).

113Analysis here would address the following sorts of practices: qualifying all exchanges as sales, so there can be no recording of outputs not for sale; seeking a positive delta between the sale price of inputs and the sale price of outputs, distributing this delta among shareholders, measuring an agent’s credit worthiness and making valuations of investors dependent on this delta, and making the rate of return or interest the mode of commensuration and the calculative information that informs agent decision making.

114A tape measure can verify that some spoons are 20 cm long and others 22 cm. No computation is needed. But to say one spoon is worth $2 and another $12 rests on social conventions of attributing value.

115In Chapter 1 of Capital, Marx referred to the relative equivalent forms of value, with the equivalent form as the benchmark against which other commodities are measured. Money becomes the ‘universal equivalent.’

116The unit of exchange and the unit of credit are similar, in the way a 100 dollar bill and a 100 dollar check are similar. Even though they both use the dollars as the measurement, they are two distinct instruments that pertain to two distinct accounts and two distinct risks. This distinction is clear from an accounting perspective, although not so much from a general use perspective.

117On tick time, see Chapter 3.5.

118The principle of standardized capitalist accounting first emerged in the 1850s, along with the legalization of joint stock companies (companies with shareholders) and limited liability. Investors needed standard performance metrics so that they could compare corporations and make informed investment choices and state protection against responsibility for the legal consequences of corporate actions. We know that these standard metrics, conventions and rules have been constantly evolving since then, but the connection of ledgers to profit has remained throughout. See, for example, Chiapello (2007), Levy (2014), Hopwood and Miller (1994) and Bryer (2000). Of course the proposition is not that everything in a capitalist society is expressed through profit criteria, but that this is the defining social feature of the era. Activities outside profit criteria are interpreted through the discourse of subsidies (and taxes), philanthropy or being classified simply as ‘non-economic.’

119Current conventional accounting can adopt a unit of ‘capital’ as its measure because capitalist accounting has been built for the specific purpose of defining and measuring ‘capital.’ This is the accounting dimension of the so-called ‘Cambridge Critique’ of capital theory which argues, in essence, that there is circularity in the conventional theory of capital: the value of capital cannot be specified until its rate of return is known and its rate of return cannot be known until capital is valued. See G.C (Harcourt 1972).

120It should also be noted in this context the trillions of dollars (or other fiat currency) of central bank ‘quantitative easing,’ for the explicit purpose of propping up liquidity in financial asset markets.

121This point is central to Sraffa’s critique of Hayek: that when supply and demand are not in equilibrium, there is a difference between the spot rate and the forward rate. This spread forms the concept of commodities having an ‘own rate of interest’ (Sraffa, 1932: 50). This framing fed into Chapter 17 of Keynes’ General Theory (1936).

122Marx would make the same claim.

123Reference here is to Marx’s circuits of capital in Volume II of Capital (1885, Part 1) and our own interpretation of a performance circuit in Chapter 11.1 and 11.2.

124See the condition of recognition, described in relation to outputs, but applying in the same way to credit, in Chapter 4.3.

125Although this phrase could describe a Local Exchange Trading Systems (LETS), where the term ‘mutual credit’ is used to describe the creation of IOUs, we are referring to scalable, tokenized credit.

126This isn’t the skeptic’s view of banks and money creation, it is the view of the Bank of England. See McLeay, et al (2014) and Bank of England (2014).

127Note the definition of shadow banking in footnote 24.

128Fleischman et al.(2020) offers an interesting twist on this proposition: the identification of credit loops which could be cleared by the temporary injection of an agreed monetary unit.

129It is only an appearance, and should always be acknowledged as such.

130Reference here is to a value theory of performance (Chapter 4.5).

131The standard source of this critique is Graeber (2011).

132His view was that while money could logically be denominated in any unit that has its own rate of interest (for example corn or coal, where the rate of interest is the change in its own price), the state’s money is superior for it is generally accepted. See Keynes 1936: Ch.17.

133See López, J. ‘Market offers: Distributed trading protocol.’ http://marketoffers.manifold.one

134Here we are in parallel with Marx (1939: 259), explaining the development of the concept of capital:

. . . it is necessary to begin not with labor but with value, and, precisely, with exchange value as an already developed movement of circulation.

135But note the caution expressed in Chapter 2.2.

136This and the following chapter—indeed the whole framing of token markets—draws on the ‘money view’ of economic analysis of Perry Mehrling (n.d.). For a summary see Saeidinezhad (2020).

137See López, J. ‘Market offers: Distributed trading protocol.’ http://marketoffers.manifold.one

138Liquidity comes with the capacity of the matching algorithm to increase matching opportunities.

139The liquidity token is different, for it is defined precisely by its universal expression.

140Weather derivatives, for example, trade spreads on indices of frost, temperature, etc.. Sports betting involves trading spreads on all sorts of game metrics, not just the final outcome. These are illustrations of non-price indices constructed to describe an underlier of which there is no owner. What is interesting here is that quantification counts ‘events’: the number of times X happens over a period, whether X is a frost or a tackle in a football game. Quantifying things by how often they occur—‘events’—is at the core of the way we define performances (see Chapter 5.3). If we use the occurrence of events to measure time, we are in the domain of what financial markets call ‘tick time’ (see Chapter 3.5).

141On claims to ‘fundamental value,’ see esp. Chapter 12.3 and Appendices 5.1 and 12.2.

142Each staking contract will specify its particular version of these participation rights.

143Readers who see this proposition as reminiscent of Keynes’ critique of stock market speculation (trades motivated by ‘other people’s opinions’) are invited to see Appendix 5.1.

144Economic textbooks want to explain money via a logical evolution from barter, and the growing complexity of economic transactions enabled by money. Anthropologists are inclined to emphasize the origins of trade in credit and the gift, bringing focus to the time interval in trade.

145Credit tokens are not designed to store value; indeed with no yield, their main risk is downside: the risk of default of the issuer. Default would be the event of the issuer not being able to provide/create its outputs, and not necessarily because of insolvency. For as long as an issuing agent creates value, the markets will adjust both the price of the offer and the reputation rating of the agent, indeed to the point that the agent may be no more than an issuer of credit. But as long as there is any demand for its commodity tokens, liquidity tokens will be matched until cleared.

146See footnote 71 for our clarification of the use of the term ‘commodity.’

147Perry Mehrling’s lectures on the ‘Money view’ make use of these types of diagrams. See http://sites.bu.edu/perry/

148Flows of stake in a secondary market occur via commodity tokens, where stake is now a ‘commodity’ to be exchanged.

149Marx (1885: ch.4), described capital as a social relation of value:

It is a movement, a circulatory process through different stages, which itself in turn includes three different forms of the circulatory process. Hence it can only be grasped as a movement, not as a static thing.

150Marx saw these circuits as describing the path of individual companies and also the economy as a whole. The latter would be seen as a set of intersecting circuits where the output of one company is the input of another; the money revenue of one industrial process is shifted to fund another, etc.. These intersections are the focus of Leontiev’s input-output analysis. We will not extend our analysis in this way, but it is consistent with that project.

151In the Marxian circuit, the return to the ‘starting point’ designates expanded value, acquired by the extraction of surplus value from labor. In our terms it would be a Pe–Pe circuit. But in the circuit of the new economic space, there is no process of surplus extraction from producers, so the circuit’s growth is via replication, not extraction.

152‘Modern portfolio theory’ tells us that the value of the whole is not simply found in adding up component prices: the composite risk profile impacts valuation.

153Outside money (Gurley and Shaw, 1960) could be fiat currencies or other forms like bitcoin. For simplicity we will represent outside money as ’ dollars.’

154In effect, the distinction between ‘noise’ and ‘real information’ (Black, 1986) cannot be known in advance.

155Despite reference here to Marx, our use of the term ‘commodity,’ explained in footnote 71.

This book is the product of joint research, discovery and iteration since we began the Economic Space Agency (ECSA) project in 2015. Its composing process has consisted of diverse intellectual inputs, revelations, impasses, often heated debate and constantly-evolving analysis. It is not easy to step into the new economic space, where we constantly find ourselves in uncertain terrain. We’ve found out it is possible only by experimenting and risking together.

Many people and insights have been a part of this process; simply too many to mention here. The three of us who have authored this book see ourselves as bearers of the influences and express our deep appreciation of all engagement. There are some people who we wish to name whose intellectual input and cooperation has been vital and is directly recognizable in this book: Jonathan Beller, Fabian Bruder, Pekko Koskinen, Ben Lee, Joel Mason and Bob Meister. #livinginthespread #ECSAforever

We thank Matt Slater for producing an audio version of two drafts of this manuscript, Pablo Somonte Ruano for designing the cover and the figures and Stevphen Shukaitis, editor of Minor Compositions, for boldly taking on our manuscript.

We’d also like to thank our families and close friends for risking with us.

Protocols for Postcapitalist Expression, written by ECSA (Economic Space Agency) thinkers Dick Bryan, Jorge López and Akseli Virtanen, marks an advance in the struggle for economic justice by directly addressing, and endeavoring to redress, the expropriation of the general intellect. The questions: Will the accumulated know-how of the species, alienated and, as Franco ‘Bifo’ Berardi (2012) put it, ‘looking for a body,’ lead to so-called humanity’s absolute demise (along with massive unrest and incalculable ecosystemic damage)? Or, is there emerging a path towards reparations, restoration, a just economy, and thus, a sustainable planetary society? It is as if the political slogan ‘No justice, no peace!’ now defines the spread of the possible futures for the global timeline.

Significantly, Protocols for Postcapitalist Expression does not give up on economic calculation or computing. It acknowledges that Economic Intelligence exists in historically sedimented economic categories and practices, but at the same time it recognizes that the form of knowledge that existing accounting creates simply cannot care about, and much less for, everyone. Composing a virtual computer, capitalist accounting processes allow for the judicious, that is profitable, apportioning of resources by producing a matrix of the fluctuating costs of production. Capital accumulation may be optimized by watching, in Hayek’s famous phrase, ‘the hands of a few dials.’ However, this calculus remains an imperial project beholden to the myriad violences of racial capitalism. In order to operationalize the world, the integration of money and computing reconstitutes the world as numbers, which is to say, as information. Arguably, we could even say, information is itself a derivative of the value-form.1 We might be forgiven for asking: does the collapse of values to exchange value, and more generally of qualities to number and thus to information have any liberatory potential whatsoever?

Those who make it to the end of the TV series Westworld (Season 4), may discover where all this derivation and calculation may now be leading. Computing represents an arbitrage on intelligence that ultimately cheapens and thus discounts life. The show’s verisimilitude, what we could think of as its late capitalist realism, serves as a kind of trailer for, or preamble to, what would appear—is appearing—as a mutation in global consciousness and capacity, due to the financialization of knowledge. Because computing is inexorably entwined with existing markets and the statistical and predictive strategies necessary for the optimization of returns, computing, in the show at least, takes over species-being as it rapidly becomes the species-grave. The only ‘creature’ who will be left to remember whatever beauty, alternative values, grace and capacity for love that may have been expressed in the centuries of human emergence, is an AI.

‘One last dangerous game,’ says Dolores to herself in the emptied world at the smoking end of four seasons of Westworld tragedies. What is that game? The series does not tell us, but the book before you might. Despite the real bleakness of the current world, we might propose, (and I think, must assume) that, here and now, some parts or fractions of ‘us’ have thus far survived the rapacious calculus of profit, and are actively seeking ways to do things otherwise. At the very least, we know that some ‘we’ or some parts of ‘us’ must now intervene if further catastrophes are to be prevented. Through the lens of economics and financial calculus, Protocols for Postcapitalist Expression proposes a new form of economic intelligence and value-computing. The text proposes measures that do not collapse the qualitative concerns for well-being and being-with of those who currently are subjects of and subject to racial capitalism. ECSA has sought a way to allow for the expression and persistence of qualitative values on a computational substrate, an economic medium, such that these values are capable of (collectively) organizing economy. In theory, it becomes possible to avoid the collapse of people’s various pursuits into the value-form that is accumulated by capital and institutionalized through oppression, and to denominate quantities in terms of socially agreed upon qualities or qualifications, which is to say, values. Precluding the collapse of values by money and information opens a path to avoiding the collapse of space, time, and species existence by computational capitalism.

This proposed re-organization of value production and thus also of sociality requires a re-casting of what we today think of as the real or natural economic forms indexed under notions including ‘equity,’ ‘credit’ and (productive) ‘labor.’ Analytically in Protocols, these traditional terms have been decomposed, grasped as social arrangements and ‘network effects,’ and recomposed such that new conceptualizations and new types of actions and inflections—new socialities—become possible, while undervalued and marginalized traditional forms of sociality might thrive. Through this process of deconstruction and recomposition of actual and social computing, the text announces a possible socio-economic, computational strategy; a ‘play,’ for economics and for futurity, in what may well be the ‘one last dangerous game.’

I say dangerous not only to refer to the current conditions on planet Earth, but because Protocols does accept aspects of the power of the value form and of economic calculus to organize societies at scale. Even as it recognizes the necessity for constellations of qualified local inputs that can persist on an economic substrate, it accepts the need for large scale organization, economic interoperability and network-specific units of account. It actually proposes that ‘economy’ needs to become more granular and more generalized. What needs to be altered is what the controls are, who has access to them, and the kind of literacy and feedback they require. While Protocols is a book of politico-economic analysis and insight, it should also be read as a script for the means to reappropriate the general intellect and thus use collective knowledge for the good of the social and ecological body. Surfaced from the unconscious operating systems of capital and reformatted, the protocols for constituting and holding equity become those for the distributed sharing of stake and thus for collectivizing risks and returns. The protocols for bank credit and monetary issuance become protocols for the peer-to-peer issuance of credit and for peer-to-peer credit clearing that is interoperable through a network of peers. The protocols for the organization of labor become protocols for the distributed assemblage of ‘performances.’ Units of account become qualified measures and indices, devoted to the emergence of interoperable qualitative values. Economy moves from stranger-based to interpersonal to collective; the imperial organization of commodities by the accumulation of capital becomes the collection organization of sociality by all.

By shifting the architecture of economy and opening it as a design space, Protocols would enable, in principle, everyone to engage newly with and access differently what is, in effect, the historical objectifications of ‘human’ thought and practice endemic to capitalist infrastructure. But we could do so at a lower cost—to ourselves and to the lives of most of us!—and thereby, slowly, reclaim the wealth of our species capacities. Modifying accounting methods can create possibilities for the shedding of inequalities sedimented into capital. Users of the protocols, finding economic alternatives in one another, may refuse value extraction, get more of what we value for less, and be able to do so without exploiting others or being exploited. Altering the computing that backgrounds our sociality, Protocols would create zones of just and convivial social production (cooperatives, ephemeral and enduring) attuned to the values of like-minded co-creators cooperating in forms of mutual aid expressive of their shared values and concerns. The result of the use of qualitative values to account for and to organize economy at once produces and requires a redesigned economic medium, and a new type of economic grammar which utilizes different rules of composition, expression and accountability.

The text is the first complete edition of this new, if still rudimentary, economic grammar; it is a kind of manual for reprogramming the economic operating system. It is also a boot-strapping strategy to take back species abilities and creations that have been captured as assets (private property and monetary instruments). These assets include machinic fixed capital (platforms, code and clouds) as well as our own collateralized futures. The text, as an offer, is designed to open a spread between capitalist and postcapitalist futures. It would allow us to wager on the option that is justice (Meister).

Whether as software, as clouds or as platforms, capital owns and rents back to us the accumulated products of human minds—our know-how and knowledge. Resituating the abstractions of economic know-how, the ECSA Economic Space Protocol described by Bryan, Lopez and Virtanen, opens the possibility for creative capacities that are unalienated from their creators, that indeed produce a commonly-held set of capacities, a ‘synthetic commons,’ particularized and directed by the living concerns of those who create it. It holds out the possibility that we might cooperate in new ways and use our performative powers to wager and indeed finance postcapitalist futures.

Consider ‘social media’—what can be clearly seen as a world-changing extractive technology grafted onto the sociality it at once enables and overdetermines. It is no secret that the mega-media platforms and their hardware make money while they make us sick. In this 21st century recasting and expropriation of the general intellect, now giving rise to financialized AI, social media platforms absorb communication and consciousness along with all of our struggles for meaning, pleasure, connection, fulfillment and liberation. Their interfaces, algorithms and data-bases convert our all-too-human aspirations into private property and thus into capital. Thus, the expression of our struggles for happiness, knowledge and communion with one another produce an alienated and therefore alienating wealth for others. All those desires for liberation end up producing their antithesis: capital. By turning our meanings into accumulated data that function for capital as contingent claims on value that we will produce in the future, the economic logic of social media turns any and all politics expressed by means of its platforms, including the politics of solidarity, love and living otherwise, into a practical politics of hierarchy and capitalist extraction. By converting all of our semiotic signals into financialized information, and thus into profits, ‘social’ media stripmines our libido, our consciousness, our imagination. In doing so, all the points of meaning and affect distributed across the socius and absorbed in one way or another by computing can thereby be grasped for performing social and organizational functions in a matrix of financialized information. This information in its architecture and management—its organizational protocols—transfers value up the stack, only to devalue the increasingly abject denizens of planet Earth. In the current world operating system, for which social media forms only one, albeit paradigmatic, layer of calculation, the meanings we create and the emotions we experience, however real and ‘immediate’ they may be, are interfaces with computing; they are productive interfaces with racial capitalism. As we perform, in the very expression of our quests for life, what elsewhere I have called ‘informatic labor,’ we experience first hand the alienation of our performative powers in the actually existing economic media of racial capitalism, that is, computational racial capitalism.

It is in this context of the latest stage of capitalism that something really interesting can finally be said about the rise of blockchain and cryptocurrency. This cryptographic medium, which has the network architecture of a messaging system, is a medium in the strong sense, akin, as I have elsewhere remarked, to photography in the mid-1800s or cinema in the early 1900s. Without turning any of the apparent key players here—the Satoshis and Vitaliks—into heroes, we might see in the ‘mankind sets forth only such problems as he can solve [sic.]’ scenario of history, a significant emergence in response to a collective demand. This emergence answers the call for a new form of economic media in order to express an alternate vision of the world. That expression, at first apparently as a monetary medium, begins to overturn the seemingly stable notions of asset, money, credit, labor, capital, derivative and many other ‘known’ financial entities implicit in, and indeed part of, the protocols of existing monetary media. The alternative vision is a programmable substrate that opens computational media to the possibility of a (re-)programming of the economic layer of computing by non-state and non-corporate actors. If we want to put a point on it, the great disruption underfoot is that economy becomes programmable from below. That, in itself, is a change in the semantics, as well as the capacities, of economy. When we recognize that our communications media are overdetermined in their function by existing monetary media, to the extent that they serve as an extension of its profit seeking logics, we begin to see that our communications media are already economic media, even though their capabilities seemed to have developed in separate and even autonomous domains.

The internet promised to democratize expression by enabling publishing and indeed broadcasting from below; but nothing about the internet changed the basic economic architecture of capitalist extraction. Indeed, in decentralizing communications, the internet extended and granularized the centralizing logics and logistics of capitalism, pushing them deeper into expressivity, thought and affect. It captures mass expressivity and converts it into capital. This colonization of the imaginary and symbolic registers results in a financialized cybernetics of mind. For democratization to happen in a meaningful way, the systems of accounts inherent in many-to-many distributed media, be they networked monetary systems (USD) or communications (Facebook), must become programmable from below. For this to happen, platforms and computing must be made programmable from below. The cybernetics of economic media must be deleveraged from capital accumulation. This transformation, and how it may be achieved, is indicated in Protocols.

Why do the cybernetics of sociality matter? For our futurity and indeed for our survival, we require an alternative to monological systems of value as expressed in national monies. We require, in short, a multi-dimensional modality of valuation not bound by the econometrics and informatic collapse inherent in capital. Multidimensional valuation implies the creation of eco-social relations that can dialogically express and preserve discourse-based values on an economic substrate, while being programmable in real time by any and all participants. (Before anyone up and leaves at the sudden thought of having to wake up and program, think first of an interface like Instagram with a tunable economic logic built in. Think also of how these already-familiar technologies of social mediation change our experiences and actualities of relation and ‘reality.’) We require the power to qualify value and to allow such qualification to both persist in an economic system and be computable. Ultimately, we will require that this system itself be collectively owned; that it be a commons.

Robust economic media, capable of heteroglossic and dialogical forms of account, are required to create a multiperspectival values-system. These media demand far more than merely a non-national variant of monetary media expressive of the capitalist value form. While the non-national dimension of cryptocurrencies introduced a significant rupture with conventional monetary substrates, platformed as they are as national currencies on nation states, their legally recognized institutions and their military police, this ultimately simple replatforming of singular denominations on distributed computing by existing cryptocurrencies is not enough. Bitcoin did in fact break the nationally managed monopolies on 21st century monetary issuance by introducing a scalable currency(/asset/option) platformed on distributed computing, but it has done, and can do, little or nothing to challenge the monologic denomination of value as a one-dimensional, that is as a unitary, currency format. Bitcoin may contest the nation, but it, and its fetishism, is all about it being an option on the value-form as historically worked up under, and as, capitalism. The question ‘Bitcoin or USD’ scarcely touches the relations of production. We must see clearly that the ‘disintermediation’ of ‘trusted third parties’ and of existing states, even if it were to be accomplished, is only one part of the picture of a liberated monetary medium, which is also to say, a liberated socius. We require the possibility for anyone to offer denominations of value that can be taken up by those who share such values as specified and indeed offered in the proffered denomination. Only then will we have a genuinely multiperspectival system.

To foreground this possibility of reprogramming a global operating system, one that is at once computational and financial, stakes a claim for a different order of significance for cryptomedia. Even Ethereum, and other ‘Layer 1’ projects that utilize smart contracts and allow for further token issuance, lack a robust grammar for composable asset creation and peer-to-peer issuance; a grammar that would allow for the on-chain preservation of qualities and the spontaneous creation of denominations. Outlining the emergence of a far more robust economic medium than what is currently wet dreamt by the ‘when Lambo?’ crypto bros going on about libertarian forms of self-sovereignty, Protocols posits a transformation not just of economy but of sociality, of subjectivity, of national politics and of ecopolitics by means of the composition and recomposition of relations of production. For those actively working in the ECSA project, what unites us as current contributors, even among our many differences, is that the radical development of economic media means that the intelligence of sociality, including that which has not been subsumed, can work for the socius, rather than be captured, farmed, privatized and put back on the market in an arbitrage on knowledge, where proprietary innovation captures the returns.

As Protocols explains, robust economic media mean that, through the equitable nomination of new asset classes and the collective denomination of values (practices which will require networked recognition, participation and validation), innovation can be collectively shared rather than capitalized. The text argues that through the sharing of stake, wealth, whose actual origins are inexorably social, can be socialized. We might add that Protocols intimates that society might ultimately be decolonized because it would, after a time, no longer be organized from the imperial standpoint of Value. The deep plurality of being, though suppressed in commodity reification and egoism alike, but in fact constituting each and all, might at last be felt and actualized. It means, in short, that the other person might at last become not a limit to your freedom, but the realization of it.

Note that no other major crypto project addresses the world in these terms. Nor do they think very deeply, if at all, about the adjoined problem of sovereignty and subjectivity, or the cybernetics thereof. It has become clearer to the participants in the ECSA project that the form many recognize as the sovereign individual is but an iteration of the value form, an avatar of capital.2 But given these economic and formal overdeterminations of agency and the reign of this type of sovereignty, we see that history, or at least collective survival, demands better chances. We have had enough of egomania and nationalism. The significance of things on the ground must be registered and economically expressed. To those ends, Protocols for Postcapitalist Expression is in pursuit of something of a different order; something that must risk the increasing granularization and resolution of computing and of the economy that computing has always expressed. Protocols must risk this granularization and resolution because that is what is already happening. But collective survival necessitates something that also simultaneously enables a detournement of extant economic logics and practices. ECSA’s analysis recognizes that the concentration of agency, whether in the form of the propertied individual or of the propertied immortal individuals called corporations and states, requires the collapse of the concerns of others, of their perspectives and of their information. It is precisely the refusal of that collapse that motivates the work presented in Protocols.

The book reveals another economic path than to have your interests collapsed as bank interest. The world is / we are ready for an economic and computational grammar that is answerable in new ways. That also means programmable in new ways, where programming by the many becomes both the way to answer economic precarity and the means to posit and preserve a plurality of qualitative values. We will answer economy with economy! The leveraged monologue of national monies, the leveraged computing architectures of privately-owned platforms, the near monopoly on who can issue what kinds of monies and types of financial instruments, including derivatives, must, if the people and ecosystems of Earth are to thrive, be delimited and, in their current forms, swept away. All of these media, we now perceive, are not only financial forms, but also informatic forms: programs in every sense of the word. They are integrated, interoperating systems, and are systems of account beholden, ultimately, to little other than profit in nationally-denominated monies; monies, we can remind ourselves, that are optimized by states and supported by their historical, institutionalized forms of organizational inequality, prisons and warlike foreign policy.

ECSA understands these systems of account, whether conceived of as interfaces, databases, financial instruments and ledgers, or as forms of money or money as capital, to be semantic forms; forms that have meaning and thus compatibility and commensurability with one another, but also, and as importantly, forms that put exorbitant pressure on life and its meanings. Today’s socio-economic systems threaten insolvency, war and extinction. They threaten all forms of meaning-making that are close to the flesh and close to the earth: desire, the imagination, consciousness, speech, writing, landscape, oceans, the body, the self. They pressure meaning, living and life, and can do so because money is composed of a set of contracts; contracts that, in effect, have subsumed, and then become, the social contract. That subsumption of the social contract by the protocols of the media of racial capitalism is the ultimate meaning of ‘the dissolution of traditional societies.’ The ECSA project, to create non-extractive, disalienating, just economy and sociality, is given new impetus with this volume and the promise it holds. A recasting of the current social contract has long been dreamt. At last, perhaps, we have an option on postcapitalism; one that, by reimagining the who and the how in the creation of contracts, will allow us to open and live in the spread between two basic futures: collectivism or extinction.

The ‘one last dangerous game’ proposed here feels correct and indeed compelling. It contends that, against disaster, our species has some chance of survival where the odds increase if we can use collective intelligence to wager livable futures. Whether in the form of decolonial resurgence, platform cooperatives, or hospice, I cannot say, but to offer the care the planet requires seems to involve an even deeper entry of the species and the bios into informatics and economics. It will not be lost on anyone that the digital operations of these very things have already done so much harm.

The book in your hands or on your screen would be a new beginning. It represents not a settling of accounts but a new mode of accounting and of being accountable to one another. A revaluation of values becomes possible by means of what is here called an ‘economic grammar,’ a grammar for the assemblage of new relations of production and thus new modes of production, and new forms of (collective) relation and self-governance. The core idea is to express values differently, such that the qualitative concerns of any and potentially all members of society may be expressed at once semantically and economically on a persistent and programmable substrate. These values may be assembled by many parties and then used to coordinate performances in accord with socially agreed upon and thus collectively mandated metrics. ‘Agreement’ here is a semantic and an economic term that, though formally accurate, is not quite adequate to affectively express the character and indeed the feel of social co-creation ECSA sees as becoming possible with a new grammar for the multitudes.

As a starting point among starting points, this text comes out of years of research at ECSA and offers the most comprehensive treatment and latest refinements of a set of protocols based on an analysis of finance, monetary networks, and the extractive processes of postmodern value production. A critique of this latter, namely the capture of semiotic and other forms of social performances by ambient computing, has enabled ECSA to endeavor to liberate social performances from such capture. ‘Performance’ in this text has emerged, dialectically as it were, as the most general act of production; what is extracted on the job, at work, on social media, in maker-spaces and in the arts. Always dialogical, performance can be taken as a category of social interaction and world-creation that names the emergent superset for other productive capacities designated by terms including labor, attention, attention economy, cognition, cognitive capitalism and virtuosity.

Counter-intuitively perhaps, the strategy includes the generalization of the power to issue—to issue financial instruments that not only fund co-creation, but create possibilities for speculation and arbitrage. A capacity to express, issue, and wager on shared futures shifts the economic ground, particularly for the smallest players who currently have no access to scripting economic protocols with which a shared future might be wagered. Can we create with and for one another’s todays and tomorrows in ways that cause less suffering and are more convivial than they could be were we to attempt to do it in the capitalist markets? Can we use our powers of co-creation to siphon value out of the capitalist system in order to build a collectivist postcapitalism? To be dramatic, part of the political answer to the obscene leverage of class power and national power on the masses, is to generalize, which is to say democratize, the power to write (co-author) derivative contracts (co-author since in these protocols, all issuance is bilateral). It is time that the masses leveraged our claims, by creating our own economic networks with a new grammar and co-created, optional rules of play. This power, made possible by platforming protocols for cooperation around values creation, allows for an extended practice of community as well as the elaboration of what Randy Martin (2013a, 2015; Lee and Martin 2016) called ‘social derivatives.’ The social derivative is a cultural instrument that is wagered in social spaces already shot through with financial volatility. It allows marginalized groups, in Martin’s words, to ‘risk together to get more of what we want.’ It is in this way that the logic contained in Protocols, that allows for the mass authorship of social derivatives, may well succeed in democratization where the internet failed.

While this power for anyone to write a derivative may sound esoteric (or even impossible and/or undesirable)—and part of the book that follows this foreword is somewhat esoteric—a breaking down the barriers to the publishing of derivative instruments means that, in a world already rendered precarious by the history of racial capitalism, everyone (not just elites) may be better able to manage their undeniable risk by organizing their economy, cooperatively and collectively, and in terms of what is valuable to them. If neoliberalism taught us anything, it is that the way out of the problems of capitalism cannot, and will never, be through the creation of more capitalism. That is why we have reimagined the cryptotoken as a set of programmable capabilities (agreements) that may be enabled only when recognized and thereby validated by peers. Their semantic content represents a wager that the relationship, or agreement, they formalize expresses something of value (anything whatever) to both parties. Because each party or agent is enabled in the network through composing themselves—by entering into a portfolio of such tokenized arrangements that are in principle limitless—the wealth of each agent then becomes a composite of the qualified interests of others.

A social derivative is a wager in the cultural sphere that responds to volatility in order that a local group can ‘risk together.’ Protocols has tried to formalize a way to express those socio-economic wagers, such that others can validate or join them non-extractively by means of their own staking and/or performance. It becomes possible, at first in principle but later practically, to nominate and denominate values and then to collectively organize socio-economic outcomes of any type that preserve, foster and realize said values: differentiable, negotiable and socially agreed upon qualitative values. This is economic expressivity. When many actors are offering such semio-economic proposals and performances on a collectively-owned economic media platform, socio-economic actors such as ourselves may engage in a multidimensional system of valuation and production attuned to anything whatever: clean beaches, dance cultures, reforestation, spoken word, prison abolition, decolonial resurgence, blood free computing, and much more. When we have a way of sharing risk, both by sharing stake (staking a performance) and/or offering performance, in a variety of qualitative outcomes by means of a scalable peer-to-peer network, we get forms of distributed risk and reward that can create a distributed form of awareness—a consciousness attuned to the specific interests of many others. This awareness results from, and constitutes, a new form of economic space and new form of economic agency: economic space agency. It will also transform subjectivity/objectivity and the membrane between self and other.

Though this new economic language may sound like it requires a learning curve too steep for the ‘average’ person, the literacy and innovation will come, just as it did and does on paradigm shifting platforms such as Facebook, Instagram and TikTok. Here, the emerging paradigm comes with the social programmability inherent in expressivity directly linked to the programmability of economy. The postcapitalist economy will be about creating new forms of social relations; new relations of production that are qualitative and non-extractive. Collectively, we will script parameters that express our semantically based, qualitative values, and collectively we will manifest these values. We may hope, and perhaps expect, that within a few years or decades, folks will not be programming their fractal celebrity; they will be programming together the nuanced worlds they actually want to live in and creating the relationships they want to have there.

There is much to learn, and much to be skeptical of. To answer the global challenges set forth by history will require the input and discernment of millions if not billions of people—it is not a technocratic endeavor. Already there are millions among us who feel the need for alternative economic forms and for a type of radical economy and/or finance that answers onthe-ground problems of access to liquidity. The movement towards basic income is just one expression of this desire. In Protocols what becomes possible is basic equity founded upon ones’ social relations. Our requirement for emancipation is not further dispossession of others or ourselves but expanded access to the social product, particularly for those who do not have it. We agree with the growing mass need for our desires and our capacities to count and be counted in ways that remand the benefits to those who sustain the world and remake it everyday.

It is not lost on us that, in the current economic calculus, a tree, an individual and even a people can be worth more dead than alive, more incarcerated or encamped then free—and we hardly need to mention deforestation, police killings, settler colonialism and genocide to make the point here. But this book, though still incomplete in significant ways and offering more of a possible way forward than any as yet definitive answer, offers what approaches a concrete plan; one that may move readers from increased eco-social literacy to active participation in building an alternative economy. It would organize social participation that will create greater literacy and expressivity even as it endeavors to collectively create and thus instantiate, a new economic medium—an economic medium for the expression and collective management of a postcapitalist economy; a medium that is socially and ecologically responsive, which is to say, increasingly non-extractive because its interfaces are made to be just. The entire project stands or falls on this wager. However, that said, the book is but a seed, one that only collective uptake, and with it collective revision, can nurture and grow.

Lastly, the desire for non-, ante-, anti- and/or post-capitalism is in no way an invention of this text; what feels new here is the method. I would say that it proposes a new way to mobilize what Harney and Moten (2013) call the general antagonism, and with it, a new form of revolution. What would it be? A detournement of financial processes and tools, a slow takeover of the economic operating system occupying planet earth by those whose interests have been collapsed into bank interest. Indeed, it is the incapacity to do just this granular and collective reformatting of the economy that has marked the failure of previous revolutions. Thus far, beyond the initial desperation, beauty and romanticism of revolutionary movements, we have mostly had various efforts at a seizing of the state that result in the reintroduction and replication of the gendered, racial and hierarchical logics of capitalism. From the Soviets, to the PRC, to scores of post-colonial states, we are familiar with the outcomes. The limitations were both of imagination and technology; movements weighed down by default notions of centralization and bureaucratic organization, notions that informed both emergent states and the discrete state computing that would develop to run them and all the others. This time, with another century of struggle and know-how, if we all listen to history and to the claims of the denizens of Earth, things may be different.